STILLBILDER / STILLS

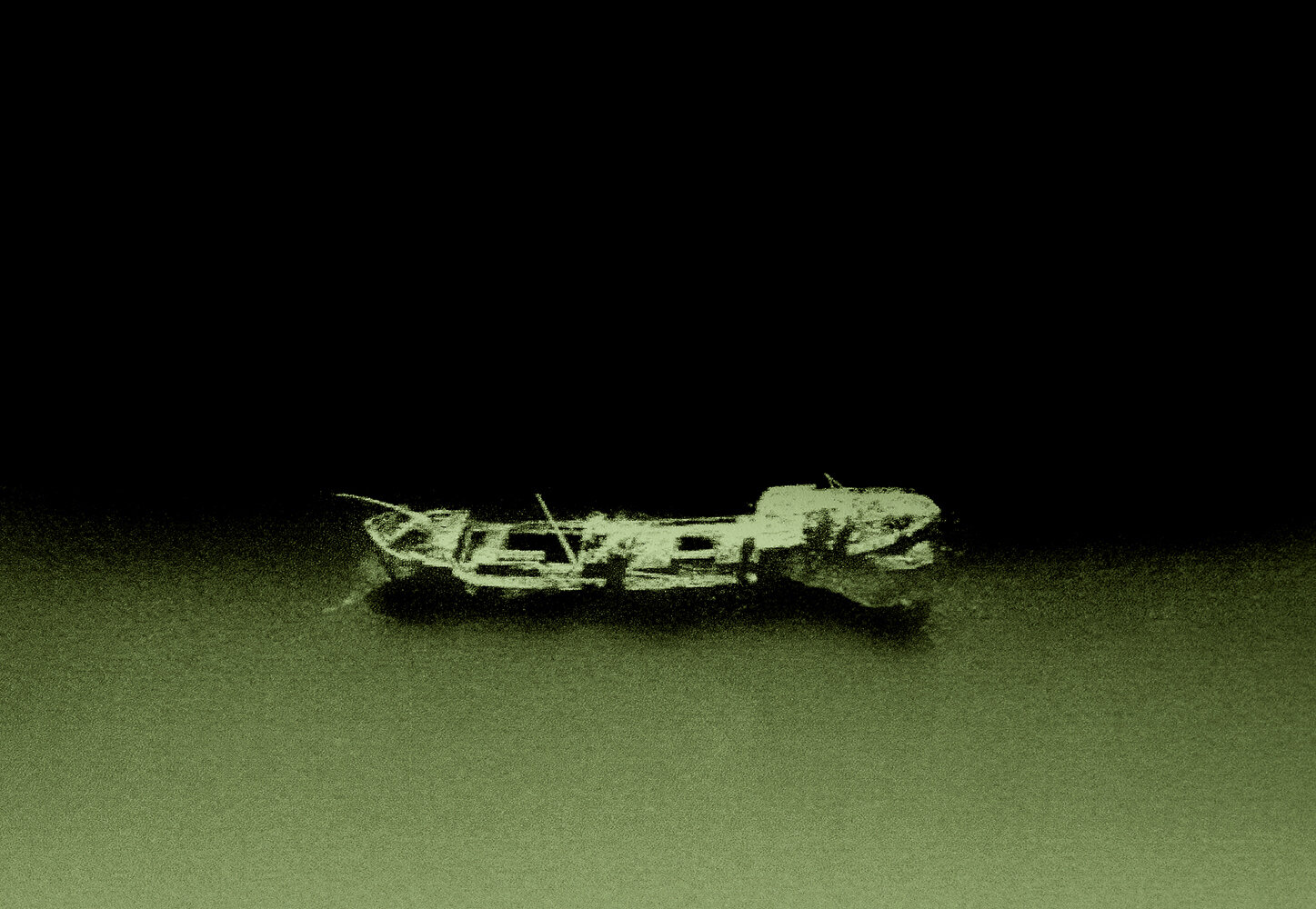

Those artworks has been made possible through a collaboration with Carl Douglas and Deep Sea Productions. Since 2005 I have continuously been taking part in their expeditions and in collaboration with the company Marin Mätteknik we have been scanning parts of the Baltic Sea. This has led to the discovery of a large number of sunken ships.

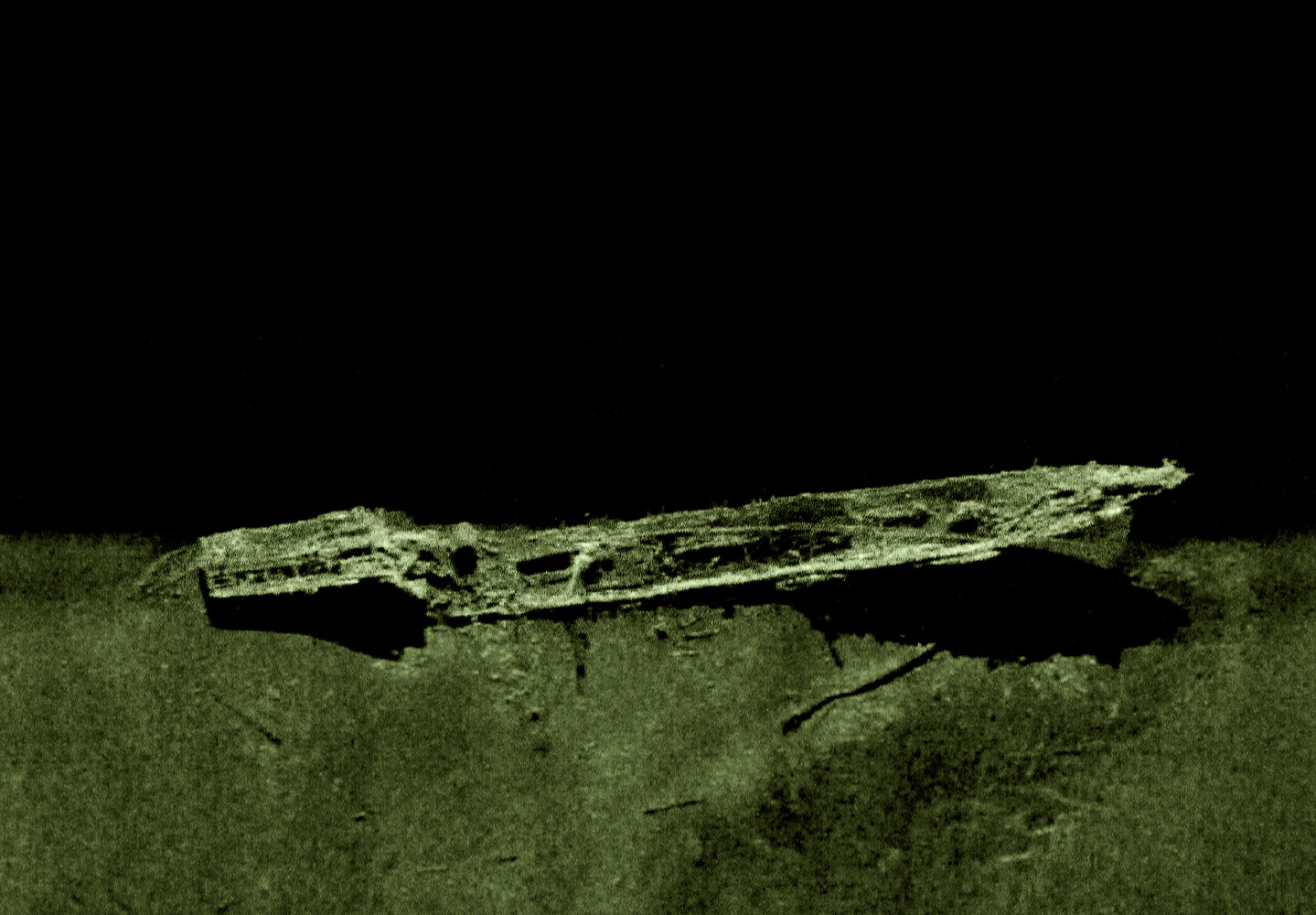

Throughout the centuries the seas, lakes and rivers have been traversed, goods have been exchanged and contacts have been made in the emerging towns and trading ports along the routes. Many ships that sailed out to sea never came back, they became victims of hurricanes or war. An outline that emerges suddenly from the normally smooth and even lower graph on the sonar equipment makes us suddenly aware of this. In thousands of otherwise anonymous places beneath a non-disclosure surface rests shipwrecks that, after moments of desperate struggle and chaos, have been frozen in the stillness of the depths of the ocean when ships and crew lost out against a powerful sea.

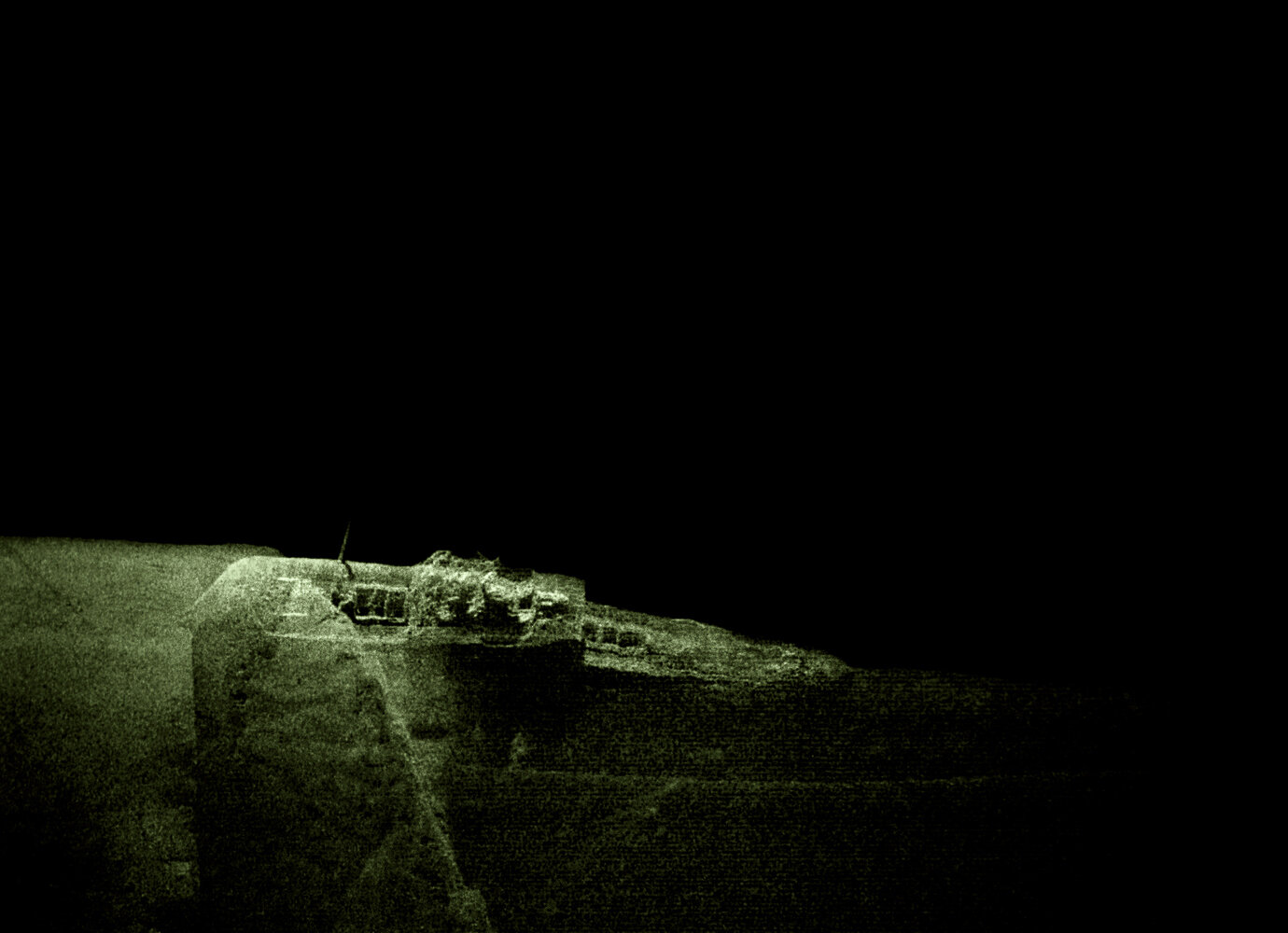

A sidescan-sonar is a marine technological instrument scanning the seabed using diagonal sound-waves that are being interpreted by a computer that turns them into an image. An objective “gaze” is directed down towards something that is impossible for the human eye to see and it is registering a world beyond the normally accessible. Ships that never reached their destinations suddenly emerges on the screen; time-capsules that have been left behind in the depths of the sea becomes visible again. The sound-waves that reaches down through the dark waters returns with echoes of an apocalyptic history.

The shipwrecks do not only bear witness of human activity but also about how nature takes over and reclaims what we have left behind. A sunken ship soon becomes its own ecosystem where plants and animals establish themselves. During all ages fishermen have been laying down their fishing nets in the proximity of shipwrecks as they quickly become an excellent habitat for fish and other sea living creatures. As soon as a ship has sunk the process of breakdown starts and the time-scale for this varies between different locations depending on factors such as the level of oxygen, salt water, tides and currents. In the Baltic Sea a shipwreck from a wooden ship can become extremely old, as there are no wood eating ship-worm present in these waters. The sunken ships becomes a home for a variety of marine species but it can at the same time be a threat to them. Fishing nets and trawls can get caught in the wreck, they remain there and continues to catch fish, seals and other mammals. Many sunken ships also contains large quantities of oil and other hazardous cargo that can be dangerous to the environment, leaking out into the sea when tanks and containers are corroding. The slow but inevitable breaking down of materials that human beings have, intendedly or unintendedly, left behind is continuing to take place down at the bottom of the sea. This reminds me of concepts such as Land Art and Entropy and of the monumental art works created by Robert Smithson in the 1960´s and 1970´s where the concept of entropy as a pattern for degradation was a central theme. If I would come back and scan some of the wrecks that I have recently seen in, say, 20 years, then this image would be completely different. Down in the dark, deep sea an unseen process is taking place when structures gradually collapses and hull and deck eventually implodes. The images created by sound waves have a number of dimensions and aspects, they tells us about our history and about how nature in the end always reclaims what civilisation has created. They tell us about burial places, threats to the environment and ecosystems. It is also possible that the images can be seen as a documentation of a kind of unintended Land Art that was never created to be shown.

Dessa verk har kommit till genom samarbete med Carl Douglas och Deep Sea Productions, som efter flera års sökande återfann den försvunna svenska Dc3:an. Jag har sedan 2005 kontinuerligt deltagit i deras expeditioner då de tillsammans med företaget Marin Mätteknik sökt av områden i Östersjön. Detta har resulterat i upptäckten av ett stort antal förlista fartyg.

Genom århundraden har haven, sjöarna och vattendragen trafikerats, varor bytt ägare och kontakter knutits mellan människor i de framväxande städerna och handelsplatserna. Många fartyg som seglade ut nådde aldrig sina destinationer utan blev offer för stormar eller sänktes i krig. En plötsligt uppskjutande kontur från den annars jämna bottenkurvan på ekolodet gör oss påminda om detta. På tusentals anonyma platser under en intet avslöjande vattenyta vilar vrak, som efter ögonblick av desperat kamp och kaos frysts i havsdjupens stillhet då fartyg och besättningar förlorat mot ett övermäktigt hav.

En sidescan-sonar är ett marinteknologiskt instrument som läser av havsbotten med hjälp av diagonala ljudvågor vilka omtolkas i en dator till bild. En objektiv ”blick” riktas ner mot någonting det mänskliga ögat ej kan se och registrerar en värld bortom den åtkomliga. Fartyg som aldrig nådde sina destinationer framträder plötsligt på skärmen, tidskapslar som lämnats åt djupens långsamma nedbrytning blir åter synliga. Ljudvågorna som tränger ner genom det mörka vattnet vänder tillbaka med ekon av en apokalyptisk historia.

Skeppsvraken vittnar inte endast om mänskliga förehavanden utan även om hur naturen återtar det vi lämnar efter oss. Ett sjunket fartyg blir snart ett eget ekosystem när växter och djur etablerar sig där. Genom århundraden har fiskare lagt sina nät vid vrak, vilka snabbt blir tillhåll för fisk. Direkt efter att ett fartyg förlist börjar nedbrytningen vars takt bestäms av lokala faktorer så som syrehalt, salthalt, tidvatten och strömmar. I Östersjön kan trävrak bli mycket gamla tack vare avsaknaden av den trä-ätande skeppsmasken. De sjunkna skeppen blir till hem för olika arter men kan samtidigt utgöra ett hot mot dem. Fiskenät och trålar fastnar i vraken och dessa så kallade spöknät fortsätter sedan att fånga fisk och sälar. Många vrak innehåller även stora mängder olja och annan miljöfarlig last som riskerar att läcka ut när tankar och containrar rostar sönder. För mig blir de förlista fartygen som ett slags ofrivillig Land Art. Tankarna går till konstnären Robert Smithsons monumentala verk från 60- och 70-talet där begreppet entropi så som ett nedbrytningens mönster var centralt. Om jag skulle skanna några av de vrak jag nu har bilder av, om säg 20- eller 30 år skulle de bilderna bli annorlunda. Nere i de mörka djupen sker obevittnade processer när konstruktioner faller samman och däck och skrov slutligen imploderar. Sonarbilderna har många aspekter. De berättar om vår historia och om hur naturen återtar det vi lämnar, om begravningsplatser där nere och om laster som hotar miljön. Möjligen kan de också ses som dokumentation över en oavsiktlig Land Art som aldrig var ämnad att bli till.